|

Here is report on a visit

to Győr

from Gila Miriam Chait.

(We received the report thanks to Stephen

Schmideg, Melbourne, Australia)

When our family of four left

Hungary

in December 1956 in the wake of the uprising in October that

year, we stopped off at

Gyor

on our way to the border with

Austria

from

Budapest

. I wonder if it

occurred to my father at that time that on our way out of

Hungary

we were passing through the area where our Reichenfeld

ancestors first settled some two hundred years

previously and where they had continued to live for several generations.

We visited

Hungary

in August 2002 by car and had the chance to explore the

places mentioned in the microfilmed Jewish records of births, marriages and

deaths kept at Gyorasszonyfa where my ggrandfather Adolf and gggrandfather

Josef/Juda were born.

Following the advice of Marianna, a Jewish lady

who still lives in

Gyor

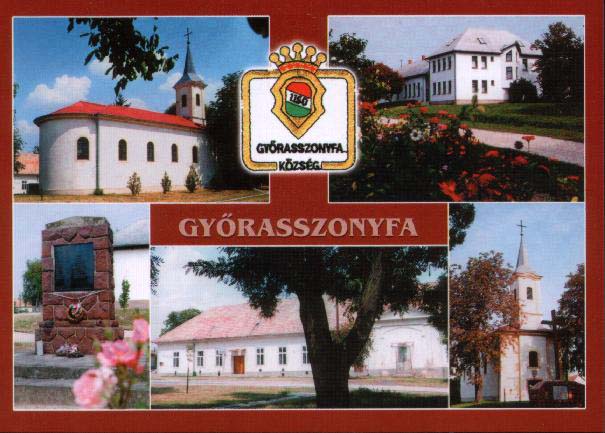

, we sought out the mayor’s office in Gyorasszonyfa,

where our Reichenfelds lived in the first half of the nineteenth century, and

where they might well have taken up the surname.

The building housing the office was erected in 1848 and therefore part of

the village when our ancestors lived there, together with the church, which was

built in1793. The mayor was very

pleased to see us and knew the name Reichenfeld straightaway.

He spent a great deal of time with us, telling us about the history of

the village and the Jewish community which existed there from the beginning of

the eighteenth century until the summer of 1944, when the Jews still living in

the village were deported to Auschwitz by the Nazi occupiers.

He took us to see the joint memorial the village has erected to the

murdered Jews and the members of the village who lost their lives on the

battlefield, listing in alphabetical order the names of all those who died.

He also showed us where the synagogue and Jewish

school had once been and gave us some literature containing very interesting

historical details.

Archeological remains show that the site was settled from as early as the

Stone Age and the earliest mention

of the village by name dates back to the 12th century:

The name Asszonyfa (lady’s village) indicates that it belonged to a

queen. The prefix

Gyor

was added later to distinguish it from other villages with

the same name. The village was

destroyed during the Turkish conquest and occupation of

Hungary

at the end of the sixteenth century, but re-established at

the beginning of the 18th century.

The mayor thought that it was at that point, soon after the rebuidling of

the village, that Jews settled there: he had no idea where they came from, but

it is quite likely they came from eastern

Austria

,

Bavaria

or

Moravia

, based on documented patterns of migration.

According to the census taken 1784-7 by order of the Habsburg Emperor

Josef II, the population of Asszonyfa at that time was 394, consisting of 90

families residing in 59 houses. By

1851, the year when the Jewish records begin, the population of the village had

more than doubled to 810, of whom 273 were Jewish, making up over a third of the

total population. After that the

population of Asszonyfa declined – a contributory factor may have been a

big fire in 1862 which appears to have destroyed most of the village.

Adolf Reichenfeld would have been 16 at the time of the fire - I wonder

how it would have affected his life: perhaps the family home was burnt down and

maybe some of their goods destroyed. There

are no more entries for deaths in 1862 than in other years, so there don’t

seem to have been a lot of lives lost, or at least not among the Jews of the

village. The Jewish population

of the village declined more steeply than the overall population.

I found some figures for 1892 on the website of the

university

of

Debrecen

: the total

population was down from 810 to 532, while the Jewish population had declined

from 273 to 73.

The rend seems to have been for them to move to bigger villages, towns

and cities. By 1944 only a dozen or

so Jews remained and the deportation of these Jews by the Nazis brought to a

final close the history of Jewish settlement in Gyorasszonyfa.

The book the mayor gave us contains an extract from a school

inspector’s report from the second half of the 19th century,

although the exact date is not given. Conditions

and equipment in the village school are described as woefully inadequate, and

worse still in the small Jewish school, a dark and damp hole covering an area

four paces by five, with 12 pupils sitting on two benches on either side of a

single table, the only piece of equipment being an old faded calculating board.

Three children of compulsory school age did not attend.

The inspector was not happy that the language of instruction was mainly

German and Hebrew, with only a little time devoted to Hungarian.

He wanted the language of instruction to be exclusively Hungarian; he

also demanded a dry well-lit class-room with a black-board and wall charts, a

globe, maps of

Europe

and

Hungary

as well as an outdoor area for physical exercise.

If these reforms did not take effect he threatened to close down the

school and compel the children of compulsory school age to attend the

village’s Roman Catholic school. It

would be interesting to know what the outcome was.

Later, under the Communist regime, the village lost its school, but since

the end of the

Soviet Union

the village has been trying to reassert its identity and has

re-established its own school, naming it after a Hungarian poet and writer.

What was left of the Jewish cemetery in Gyorasszonyfa was in a very sorry

state. It was so overgrown that it

was hard to see anything, but we did find the graves of a Reichenfeld husband

and wife: Jakab Reichenfeld, who died in 1884, and Barbela nee Krausz, who died

two years later. Both deaths are

recorded in the microfilmed Jewish

records. It is sad to think that

this derelict piece of ground with a few neglected graves is all that is left of

a cemetery where the registers show that several hundred people were buried.

Our guide told us that although the village could not afford to restore

and maintain the cemetery, they would not build on the site or destroy what

remains of it. Since our visit he

has written to tell me about plans to have the cemetery restored and maintained

and a memorial erected listing the names of those buried there with no visible

headstone.’

He might be willing to send

anyone who is interested a copy of the ‘Emlekkonyv’ if they were to

write to him. His name is Valiczko

Mihaly and the address is Polgarmsteri Hivatal, Hunyadi ter 18, 9093

Gyorasszonyfa

,

Hungary

.

Marianna, the lady who had given us advice about our trip, gave us a

guided tour of the synagogue and Jewish cemetery at

Gyor

. In the cemetery

there was a plot which records indicate was the burial site of a Reichenfeld

Adolfne, but as nothing at all was left of the grave we were unable to ascertain

whether or not this was the grave of my great grandmother Rozalia.

I made a Kel Mole Rachamim for her in any case and made a small donation

towards the upkeep of the cemetery. It

was good to see that there was still a Jewish presence in the city and that the

synagogue and cemetery were well maintained.

Our visit to the area certainly helped me to try to imagine what the lives

of my ancestors who had lived there might have been like.

*

* * *

|